This week’s Photo Eye auction video by Eric Miles prompted me to tackle a perversion of art history scholarship which has taken root in American auction houses and galleries since the Steven Kasher Gallery show in 2008 of Wingate Paine’s photographs.

In the video referring to Wingate Paine’s book ‘Mirror of Venus’ (1966) Mr Miles describes Paine as being “As American as baseball” and credits him with creating photographic icons of the 60s sexual revolution. Eric Miles goes on to identify Paine as being the American branch of the 60’s style revolution happening in London in particular drawing a parallel with the movie ‘Blow Up’ and the fashion designs of Mary Quant.

There is only one problem with this heroic American view of Mr Paine’s images – it’s a lie. In a lifetime of observing Sam’s influence and influences, I have never come across another photographer whose entire artistic ‘signature’ has been based on copying Sam’s work to the same extent as Mr Paine. Of course Sam is highly referenced, more today than ever, and photographers like Tom Munro or Mario Testino have copied Sam’s work copiously. The thing is that next week Mr Munro will be all over Avedon and the week after that Guy Bourdin then Newton etc. Mr Paine on the other hand has Sam’s ‘style’, not to mention specific ideas, all over his entire career.

Wingate Paine – an ‘acquired’ artistic signature

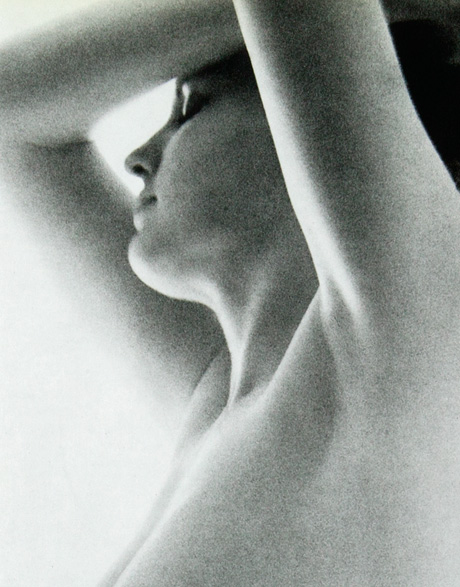

From Five Girls by Sam Haskins (1962)

From Five Girls by Sam Haskins (1962)

From Five Girls by Sam Haskins (1962)

From Five Girls by Sam Haskins (1962)

From Five Girls by Sam Haskins (1962)

From Five Girls by Sam Haskins (1962)

Wingate Paine (circa 1965/6 or later)

Wingate Paine (circa 1965/6 or later)

Gill and Curl from Five Girls by Sam Haskins (1962)

Gill and Curl from Five Girls by Sam Haskins (1962)

Wingate Paine (circa 1965/6 or later)

Wingate Paine (circa 1965/6 or later)

The first content page of ‘Five Girls’ by Sam Haskins (1962) and below a close up crop.

The first content page of ‘Five Girls’ by Sam Haskins (1962) and below a close up crop.

Front cover of ‘Mirrror of Venus’ by Wingate Paine (1966)

Front cover of ‘Mirrror of Venus’ by Wingate Paine (1966)

At some basic level I don’t really have a problem with Paine’s work in its own right. Deep down it is just how the art world works, especially in fashion and glamour with its ubiquitous ‘mood board’ syndrome. Mr Paine made a living as a photographer, which on its own is fine. There are however two problems here, one is art historical accuracy and correct credit and the other is understanding the difference between plagiarism and ‘reference’ or ‘influence’. There is a very important and distinct difference, not just for reasons of academic sequencing, but because the work of master artists who evolve their art form automatically carries a power which is self evident – especially over time.

Apart from the need for veracity in tracing the history of style and ideas there is another magical lie-detector at work here – the camera itself. And, this test, Mr Paine passes with credit. Photography perhaps more than any other art form provides a direct view onto the artist’s heart. Mr Paine couldn’t resist putting his hand into the cookie jar of Sam’s creativity – all the way up to his elbow – but in the process of stealing he revealed a truth. He really did love women and the photographic process, it is just sad that he couldn’t find his own voice to sing their praises.

‘Mirror of Venus’, Mr Paine’s compendium of work was published in 1966, four years after Sam’s ‘Five Girls’ and two years after ‘Cowboy Kate and Other Stories’. Mr Paine’s book went on to be reprinted several times and remained a best seller well into the 70s, which is an important commercial underpinning to the self delusional process of stealing an artistic identity – copying is profitable! It should however be borne in mind that at this time Cowboy Kate was in the process of selling nearly a million copies worldwide – probably a photo book record – and the widespread praise and exposure of Kate and Sam’s other work no doubt played a part in helping to boost sales of ‘Mirror of Venus’.

The debt that Mr Paine owes to Sam cannot be overlooked by contemporary commentators as serious and highly regarded as Photo-Eye. Which is not to say, in the overall evolution of ideas, that Sam’s thinking was not passed on to some photographers through Wingate Paine’s book. Until that is, those who thought that Paine was an American ‘original’ acquired libraries that were worth more than their cameras. At which point one would hope that they ‘discovered’ the true originator of the ideas and style adopted by Paine simply by looking at ‘Five Girls’ and ‘Cowboy Kate’ by Sam Haskins.

The question of where copying ends and influence or evolutionary reference starts is perhaps best answered by looking at the history of all ideas and even at evolution itself. The question is answered with eloquence in the series of four online videos by Kirby Ferguson, ‘Everything is a Remix’. His constant return to the mechanics of evolution, ‘Copy – Transform – Combine’ is immensely useful in clarifying the difference between copying or plagiarism and evolution or influence. In the art world, if you just ‘Copy’ or just ‘Copy and Combine’ that will inevitably produce a failure, a very low voltage version of something else which has real power. Without transformation there is no evolutionary ‘influence’. Real evolution always transforms and always leads to new life forms. That’s life and that’s art.

Below: An example of copying and combining without ‘transforming’, a case of 1+1=0.5

Sunday from ‘Other Stories’ in ‘Cowboy Kate and Other Stories by Sam Haskins (1964)

Sunday from ‘Other Stories’ in ‘Cowboy Kate and Other Stories by Sam Haskins (1964)

Cover of ‘Cowboy Kate and Other Stories by Sam Haskins (1964)

Cover of ‘Cowboy Kate and Other Stories by Sam Haskins (1964)

Wingate Paine (circa 1965/6 or later)

Wingate Paine (circa 1965/6 or later)

Sam Haskins and Jean-Loup Sieff a cross fertilising dialogue of influence

In terms of artistic merit the creatively ‘thin’ nature of Mr Paine’s work stands in sharp contrast to the work of those artists like Jean-Loup Sieff – also referenced in Eric Miles video – who was both an influence on Sam and influenced by him. Mr Sieff was a master photographer whose work carried his own distinctive, original ‘signature’. In the creative environment of Mr Sieff’s mind or Sam’s or any master photographer’s, influence is always ‘transformed’ never just copied or combined.

Mr Sieff started his career as a photo journalist and a member of Magnum and like many other photographers, ‘Five Girls’ was more than an inspiration to him. Like all ground breaking photography, it constituted permission to see, feel and think in a new way. Jean-Loup’s own genius and common values and subject matter (nudes, nature, meticulous lighting, eroticism) led to a long running cross fertilisation between himself and Sam. Although Sam featured in a book that Mr Sieff produced of contemporary photographers, they sadly never met.

It’s been impossible for me to tell which of the following shots came first but it really doesn’t matter – there was an influence dialogue between Sam and Jean-Loup. Both these shots explore ‘frame within a frame’, nudes and a single light source.

Jean-Loup Sieff 1970s

Jean-Loup Sieff 1970s

“Diagonal Apple” by Sam Haskins 1970s

“Diagonal Apple” by Sam Haskins 1970s

Again, not sure of the dates of the Sieff image and again it doesn’t matter.

Tea Break by Sam Haskins from Cowboy Kate and Other Stories (1964)

Tea Break by Sam Haskins from Cowboy Kate and Other Stories (1964)

Jean-Loup Sieff 1960s

Jean-Loup Sieff 1960s

Here there is little doubt that the Haskins image was published first.

‘Card Cheat from Cowboy Kate by Sam Haskins (1964)

‘Card Cheat from Cowboy Kate by Sam Haskins (1964)

Jean-Loup Sieff (circa early 1970s)

Jean-Loup Sieff (circa early 1970s)

In preparing this post I took great care to look over the original material and as far as possible check dates. In the context of the Paine/Haskins story this revealed a very important and ironic footnote to the understanding of ‘Copy – Transform – Combine’. It turns out that in the process of stealing from Sam with both arms, Wingate Paine produced an image in ‘Mirror of Venus’ based on a photograph in ‘Cowboy Kate’ (a model sitting on an unmade bed) – just as Sam was working on ‘November Girl’ (published in 1967). It’s very likely that Paine’s copy, with its room corner set, in turn, sparked an idea in Sam’s head, for the ‘Parisian loft’ set which is among some of the best loved images from ‘November Girl’. In other words, I think he stole back from the thief! Which reinforces the Oscar Wilde insight “Talent borrows, Genius Steals” only Mr Wilde forgot to add “…and transforms.”

From Cowboy Kate & Other Stories by Sam Haskins (1964)

From Cowboy Kate & Other Stories by Sam Haskins (1964)

Wingate Paine (circa 1965/6 or later)

Wingate Paine (circa 1965/6 or later)

From November Girl by Sam Haskins (1967)

From November Girl by Sam Haskins (1967)

Ludwig